We all know how important debugging is for improving application performance and features. BrowserStack runs one million sessions a day on a highly distributed application stack! Each involves several moving parts, as a client’s single session can span multiple components across several geographic regions.

Without the right framework and tools, the debugging process can be a nightmare. In our case, we needed a way to collect events happening during different stages of each process in order to get an in-depth understanding of everything taking place during a session. With our infrastructure, solving this problem became complicated as each component might have multiple events from their lifecycle of processing a request.

That’s why we developed our own in-house Central Logging Service tool (CLS) to record all important events logged during a session. These events help our developers identify conditions where something goes wrong in a session and helps keep track of certain key product metrics.

Debugging data ranges from simple things like API response latency to monitoring a user’s network health. In this article, we share our story of building our CLS tool which collects 70G of relevant chronological data per day from 100+ components reliably, at scale and with two M3.large EC2 instances.

The Decision To Build In-House

First, let’s consider why we built our CLS tool in-house rather than used an existing solution. Each of our sessions sends 15 events on average, from multiple components to the service – translating into approximately 15 million total events per day.

Our service needed the ability to store all this data. We sought a complete solution to support event storing, sending and querying across events. As we considered third-party solutions such as Amplitude and Keen, our evaluation metrics included cost, performance in handling high parallel requests and ease of adoption. Unfortunately, we could not find a fit that met all our requirements within budget – although benefits would have included saving time and minimizing alerts. While it would take additional effort, we decided to develop an in-house solution ourselves.

Technical Details

In terms of architecting for our component, we outlined the following basic requirements:

- Client Performance

Does not impact the performance of the client/component sending the events. - Scale

Able to handle a high number of requests in parallel. - Service performance

Quick to process all events being sent to it. - Insight into data

Each event logged needs to have some meta information to be able to uniquely identify the component or user, account or message and give more information to help the developer debug faster. - Queryable interface

Developers can query all events for a particular session, helping to debug a particular session, build component health reports, or generate meaningful performance statistics of our systems. - Faster and easier adoption

Easy integration with an existing or new component without burdening teams and taking up their resources. - Low maintenance

We are a small engineering team, so we sought a solution to minimize alerts!

Building Our CLS Solution

Decision 1: Choosing An Interface To Expose

In developing CLS, we obviously didn’t want to lose any of our data, but we didn’t want component performance to take a hit either. Not to mention the additional factor of preventing existing components from becoming more complicated, since it would delay overall adoption and release. In determining our interface, we considered the following choices:

- Storing events in local Redis in each component, as a background processor pushes it to CLS. However, this requires a change in all components, along with an introduction of Redis for components which didn’t already contain it.

- A Publisher – Subscriber model, where Redis is closer to the CLS. As everyone publishes events, again we have the factor of components running across the globe. During the time of high-traffic, this would delay components. Further, this write could intermittently jump up to five seconds (due to the internet alone).

- Sending events over UDP, which offers a lesser impact on application performance. In this case data would be sent and forgotten, however, the disadvantage here would be data loss.

Interestingly, our data loss over UDP was less than 0.1 percent, which was an acceptable amount for us to consider building such a service. We were able to convince all teams that this amount of loss was worth the performance, and went ahead to leverage a UDP interface that listened to all events being sent.

While one result was a smaller impact on an application’s performance, we did face an issue as UDP traffic was not allowed from all networks, mostly from our users’ – causing us in some cases to receive no data at all. As a workaround, we supported logging events using HTTP requests. All events coming from the user’s side would be sent via HTTP, whereas all events being recorded from our components would be via UDP.

Decision 2: Tech Stack (Language, Framework & Storage)

We are a Ruby shop. However, we were uncertain if Ruby would be a better choice for our particular problem. Our service would have to handle a lot of incoming requests, as well as process a lot of writes. With the Global Interpreter lock, achieving multithreading or concurrency would be difficult in Ruby (please don’t take offense – we love Ruby!). So we needed a solution that would help us achieve this kind of concurrency.

We were also keen to evaluate a new language in our tech stack, and this project seemed perfect for experimenting with new things. That’s when we decided to give Golang a shot since it offered inbuilt support for concurrency and lightweight threads and go-routines. Each logged data point resembles a key-value pair where ‘key’ is the event and ‘value’ serves as its associated value.

But having a simple key and value is not enough to retrieve a session related data – there is more metadata to it. To address this, we decided any event needing to be logged would have a session ID along with its key and value. We also added extra fields like timestamp, user ID and the component logging the data, so that it became more easy to fetch and analyze data.

Now that we decided on our payload structure, we had to choose our datastore. We considered Elastic Search, but we also wanted to support update requests for keys. This would trigger the entire document to be re-indexed, which might affect the performance of our writes. MongoDB made more sense as a datastore since it would be easier to query all events based on any of the data fields that would be added. This was easy!

Decision 3: DB Size Is Huge And Query And Archiving Sucks!

In order to cut maintenance, our service would have to handle as many events as possible. Given the rate that BrowserStack releases features and products, we were certain the number of our events would increase at higher rates over time, meaning our service would have to continue to perform well. As space increases, reads and writes take more time – which could be a huge hit on the service’s performance.

The first solution we explored was moving logs from a certain period away from the database (in our case, we decided on 15 days). To do this, we created a different database for each day, allowing us to find logs older than a particular period without having to scan all written documents. Now we continually remove databases older than 15 days from Mongo, while of course keeping backups just in case.

The only leftover piece was a developer interface to query session-related data. Honestly, this was the easiest problem to solve. We provide an HTTP interface, where people can query for session related events in the corresponding database in the MongoDB, for any data having a particular session ID.

Architecture

Let’s talk about the internal components of the service, considering the following points:

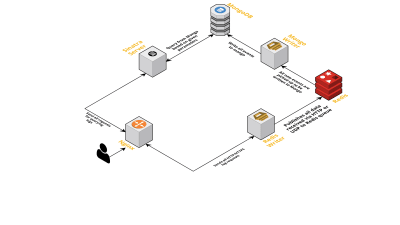

- As previously discussed, we needed two interfaces – one listening over UDP and another listening over HTTP. So we built two servers, again one for each interface, to listen for events. As soon as an event arrives, we parse it to check whether it has the required fields – these are session ID, key, and value. If it does not, the data is dropped. Otherwise, the data is passed over a Go channel to another goroutine, whose sole responsibility is to write to the MongoDB.

- A possible concern here is writing to the MongoDB. If writes to the MongoDB are slower than the rate data is received, this creates a bottleneck. This, in turn, starves other incoming events and means dropped data. The server, therefore, should be fast in processing incoming logs and be ready to process ones upcoming. To address the issue, we split the server into two parts: the first receives all events and queues them up for the second, which processes and writes them into the MongoDB.

- For queuing we chose Redis. By dividing the entire component into these two pieces we reduced the server’s workload, giving it room to handle more logs.

- We wrote a small service using Sinatra server to handle all the work of querying MongoDB with given parameters. It returns an HTML/JSON response to developers when they need information on a particular session.

All these processes happily run on a single m3.large instance.

Feature Requests

As our CLS tool saw more use over time, it needed more features. Below, we discuss these and how they were added.

Missing Metadata

Gradually as the number of components in BrowserStack increases, we’ve demanded more from CLS. For example, we needed the ability to log events from components lacking a session ID. Otherwise obtaining one would burden our infrastructure, in the form of affecting application performance and incurring traffic on our main servers.

We addressed this by enabling event logging using other keys, such as terminal and user IDs. Now whenever a session is created or updated, CLS is informed with the session ID, as well as the respective user and terminal IDs. It stores a map that can be retrieved by the process of writing to MongoDB. Whenever an event that contains either the user or terminal ID is retrieved, the session ID is added.

Handle Spamming (Code Issues In Other Components)

CLS also faced the usual difficulties with handling spam events. We often found deploys in components that generated a huge volume of requests sent to CLS. Other logs would suffer in the process, as the server became too busy to process these and important logs were dropped.

For the most part, most of the data being logged were via HTTP requests. To control them we enable rate limiting on nginx (using the limit_req_zone module), which blocks requests from any IP we found hitting requests more than a certain number in a small amount of time. Of course, we do leverage health reports on all blocked IPs and inform the responsible teams.

Scale v2

As our sessions per day increased, data being logged to CLS was also increasing. This affected the queries our developers were running daily, and soon the bottleneck we had was with the machine itself. Our setup consisted of two core machines running all of the above components, along with a bunch of scripts to query Mongo and keep track of key metrics for each product. Over time, data on the machine had increased heavily and scripts began to take a lot of CPU time. Even after trying to optimizing Mongo queries, we always came back to the same issues.

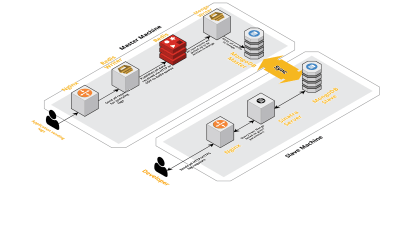

To solve this, we added another machine for running health report scripts and the interface to query these sessions. The process involved booting a new machine and setting up a slave of the Mongo running on the main machine. This has helped reduce the CPU spikes we saw every day caused by these scripts.

Conclusion

Building a service for a task as simple as data logging can get complicated, as the amount of data increases. This article discusses the solutions we explored, along with challenges faced while solving this problem. We experimented with Golang to see how well it would fit with our ecosystem, and so far we have been satisfied. Our choice to create an internal service rather than paying for an external one has been wonderfully cost-efficient. We also didn’t have to scale our setup to another machine until much later – when the volume of our sessions increased. Of course, our choices in developing CLS were completely based on our requirements and priorities.

Today CLS handles up to 15 million events every day, constituting up to 70 GB of data. This data is being used to help us solve any issues our customers face during any session. We also use this data for other purposes. Given the insights each session’s data provides on different products and internal components, we’ve begun leveraging this data to keep track of each product. This is achieved by extracting the key metrics for all the important components.

All in all, we’ve seen great success in building our own CLS tool. If it makes sense for you, I recommend you consider doing the same!

Source: smashingmagazine.com