In this guide, we’ll be implementing token based authentication in our own node.js A.P.I. using JSON web tokens.

Plan of attack

We’ll begin by:

- Setting up our development environment and initializing our express server.

- Creating our first basic route and controller.

- Fleshing out our routes and controllers to add users and login users.

- Creating a route and controller that will handle getting all users.

Finally, we’ll

- Add middleware to protect our get users route by requiring a user to be an admin and to have a valid token.

- Validate that only an admin with a token can access the protected route.

Sounds exciting? Let’s get to it then.

Setup

Before we get started in earnest, we’ll need to have a few things taken care of.

Folder structure

Here’s what our folder structure will look like:

├── config.js

├── controllers

│ └── users.js

├── index.js

├── models

│ └── users.js

├── routes

│ ├── index.js

│ └── users.js

├── utils.jsQuickly create it using the following commands:

>> mkdir -p jwt-node-auth/{controllers/users.js,models/users.js,routes/index.js,routes/users.js}

>> touch utils.js && touch config.js && touch index.jsPrerequisites & Dependencies

The only global install we’ll need is node.js so make sure you have that installed. After that, let’s install our local project dependencies.

Run the following command to initialize our package.json file.

npm init --yesInstall all our dependencies by running:

>> npm install express body-parser bcrypt dotenv jsonwebtoken mongoose --save

>> npm install morgan nodemon --save-devWhy these dependencies?

Dependencies

- body-parser: This will add all the information we pass to the API to the

request.bodyobject. - bcrypt: We’ll use this to hash our passwords before we save them our database.

- dotenv: We’ll use this to load all the environment variables we keep secret in our

.envfile. - jsonwebtoken: This will be used to sign and verify JSON web tokens.

- mongoose: We’ll use this to interface with our mongo database.

Development dependencies

- morgan: This will log all the requests we make to the console whilst in our development environment.

- nodemon: We’ll use this to restart our server automatically whenever we make changes to our files.

JWT_SECRET=addjsonwebtokensecretherelikeQuiscustodietipsoscustodes

MONGO_LOCAL_CONN_URL=addmongoconnectionurlhere

MONGO_DB_NAME=addmongodbnamehereLet’s set up our server.

Server initialization

Add the following line to your package.json file.

package.json

"scripts": {

"dev": "NODE_ENV=development nodemon index.js"

},We’ll now start our server with the npm run dev command.

Every time we do this, development is automatically set as a value for the NODE_ENV key in our process object.

The command nodemon index.js will allow nodemon to restart our server every time we make changes in our folder structure.

Let’s define the port we’ll have our server listen to in the config file.

config.js

module.exports = {

development: {

port: process.env.PORT || 3000

}

}Then set up our server like this:

index.js

const express = require('express');

const logger = require('morgan');

const bodyParser = require('body-parser');

const app = express();

const router = express.Router();

const environment = process.env.NODE_ENV; // development

const stage = require('./config')[environment];

app.use(bodyParser.json());

app.use(bodyParser.urlencoded({

extended: true

}));

if (environment !== 'production') {

app.use(logger('dev'));

}

app.use('/api/v1', (req, res, next) => {

res.send('Hello');

next();

});

app.listen(`${stage.port}`, () => {

console.log(`Server now listening at localhost:${stage.port}`);

});

module.exports = app;Run npm run dev at the root of the project and make sure the word Hello is logged when you access the uri localhost:3000/api/v1.

Now that we’re all set up, let’s move on to bootstrapping our add user functionality.

Developing our add user functionality

Let’s modify our server to accept our routing function as middleware that will be triggered on all our routes.

index.js

const routes = require('./routes/index.js');

app.use('/api/v1', routes(router));controllers/users.js

module.exports = {

add: (req, res) => {

return;

}

}Route setup

routes/index.js

const users = require('./users');

module.exports = (router) => {

users(router);

return router;

};Here, for the sake of modularity, we pass the router from our server.js file to the router that will handle all functionality related to our users.

routes/users.js

const controller = require('../controllers/users');

module.exports = (router) => {

router.route('/users')

.post(controller.add);

};All we’re doing here is passing our add controller to our router. It’ll be triggered when we make a POST request to the /users route.

Next, let’s work on defining our users model.

Developing the User Model

models/users.js

const mongoose = require('mongoose');

const bcrypt = require('bcrypt');

const environment = process.env.NODE_ENV;

const stage = require('./config')[environment];

// schema maps to a collection

const Schema = mongoose.Schema;

const userSchema = new Schema({

name: {

type: 'String',

required: true,

trim: true,

unique: true

},

password: {

type: 'String',

required: true,

trim: true

}

});

module.exports = mongoose.model('User', userSchema);To add users to our collection, we’ll require that they give us a name and password string.

Hashing users passwords

As stated before, we’ll use bcrypt to hash our users passwords before we store them.

Let’s add a line to our config file to specify how many times we want to salt our passwords.

config.js

module.exports = {

development: {

port: process.env.PORT || 3000,

saltingRounds: 100

}

}We’ll use the mongoose pre hook on save to make sure our passwords are hashed before we save them.

Add the following above the module.exports = mongoose.model('User', userSchema); line.

models/users.js

// encrypt password before save

userSchema.pre('save', function(next) {

const user = this;

if(!user.isModified || !user.isNew) { // don't rehash if it's an old user

next();

} else {

bcrypt.hash(user.password, stage.saltingRounds, function(err, hash) {

if (err) {

console.log('Error hashing password for user', user.name);

next(err);

} else {

user.password = hash;

next();

}

});

}

});Now, let’s modify our add users controller to handle adding users after being handed a name and password

controllers/users.js

const mongoose = require('mongoose');

const User = require('../models/users');

const connUri = process.env.MONGO_LOCAL_CONN_URL;

module.exports = {

add: (req, res) => {

mongoose.connect(connUri, { useNewUrlParser : true }, (err) => {

let result = {};

let status = 201;

if (!err) {

const { name, password } = req.body;

const user = new User({ name, password }); // document = instance of a model

// TODO: We can hash the password here before we insert instead of in the model

user.save((err, user) => {

if (!err) {

result.status = status;

result.result = user;

} else {

status = 500;

result.status = status;

result.error = err;

}

res.status(status).send(result);

});

} else {

status = 500;

result.status = status;

result.error = err;

res.status(status).send(result);

}

});

},

}In the above code, we connect to our mongodb database then access the name and password provided in the request by destructuring those properties from the request.body object. Remember, we can do this because of our bodyparser middleware.

Next we create a new user document by calling new on our model then in the same step add the name and password we got from the request to the new document.

We could easily have done this instead.

const name = req.body.name;

const password = req.body.password;

let user = new User();

user.name = name;

user.password = password;

user.save((err, user) => { ... }Does that seem clearer?

We exploited mongoose’s pre hook and hashed our password in our users model but we could just as well have hashed it in our controller before we called user.save

Finally, we pass a callback function into user.save that will handle our errors and pass the user back to us in our server response. We attach a handy status property in our response to let us know if the result was successful or not.

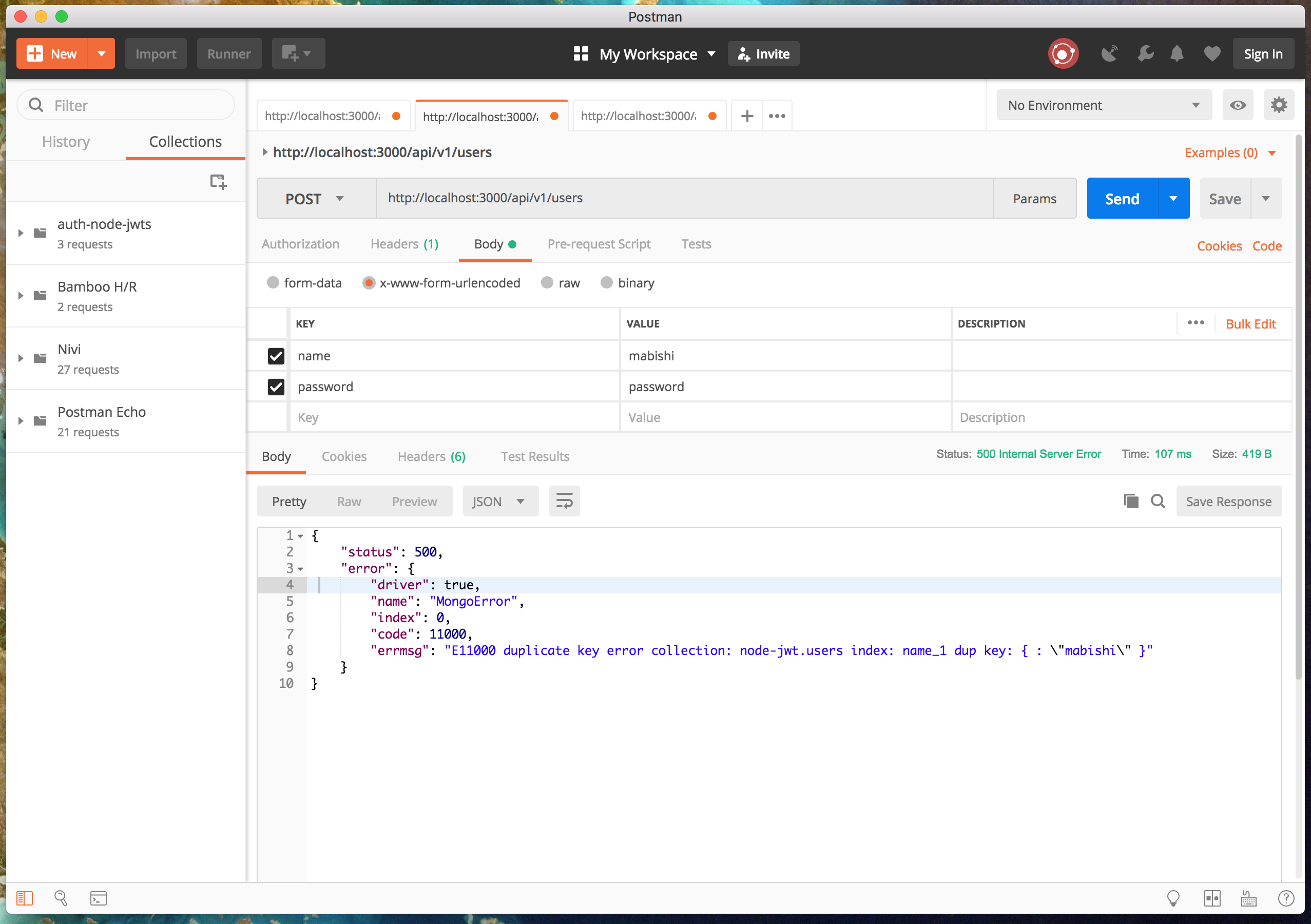

Testing with Postman

I’m using Postman to test out my API functionality but you can use any request library or application you like. Heck, you can even use curl if you’re a console purist. Cue the XBox and Playstation fan boys and fan girls. Tada!

As you can see below, we can now create users by making POST requests to the /api/v1/users endpoint.

What’s that strange string as the value under the password key? Well, that’s our password in hash form.

We store it this way because it’s safer. Hashes are ridiculously difficult to reverse.

Edit out the pre save hashing hook and see what happens. Don’t forget to put it back though. Perish the thought!

We’ll see how to verify that a user is who they say they are, using the password they give us later when we work on the /login route.

Here’s what happens when we try to create a user without specifying a password.

Here’s what happens when we try to duplicate a user.

Developing our log in user functionality

routes/users.js

const controller = require('../controllers/users');

module.exports = (router) => {

router.route('/users')

.post(controller.add);

router.route('/login')

.post(controller.login)

};Add the following import statement to the users controller.

const bcrypt = require('bcrypt');Then, let’s add the login controller that will handle our requests to the /login route.

login: (req, res) => {

const { name, password } = req.body;

mongoose.connect(connUri, { useNewUrlParser: true }, (err) => {

let result = {};

let status = 200;

if(!err) {

User.findOne({name}, (err, user) => {

if (!err && user) {

// We could compare passwords in our model instead of below

bcrypt.compare(password, user.password).then(match => {

if (match) {

result.status = status;

result.result = user;

} else {

status = 401;

result.status = status;

result.error = 'Authentication error';

}

res.status(status).send(result);

}).catch(err => {

status = 500;

result.status = status;

result.error = err;

res.status(status).send(result);

});

} else {

status = 404;

result.status = status;

result.error = err;

res.status(status).send(result);

}

});

} else {

status = 500;

result.status = status;

result.error = err;

res.status(status).send(result);

}

});

}Above, we query our collection to find the user by their name. If we find them, we use bcrypt to compare the hash generated using the password they’ve given us and the hash that we’d previously stored. If we don’t find them, we send ourselves an error.

As you can see above, we can now log in our users. As an experiment, try logging in a user without a password or with an incorrect password and see what happens.

Adding Tokens to our authentication process

Let’s add the following import statement to our users controller then work on modifying our login controller to create tokens.

As mentioned before, we’ll use these to protect one of our routes from unauthorized access.

controllers/users.js

const jwt = require('jsonwebtoken');login: (req, res) => {

const { name, password } = req.body;

mongoose.connect(connUri, { useNewUrlParser: true }, (err) => {

let result = {};

let status = 200;

if(!err) {

User.findOne({name}, (err, user) => {

if (!err && user) {

// We could compare passwords in our model instead of below as well

bcrypt.compare(password, user.password).then(match => {

if (match) {

status = 200;

// Create a token

const payload = { user: user.name };

const options = { expiresIn: '2d', issuer: 'https://scotch.io' };

const secret = process.env.JWT_SECRET;

const token = jwt.sign(payload, secret, options);

// console.log('TOKEN', token);

result.token = token;

result.status = status;

result.result = user;

} else {

status = 401;

result.status = status;

result.error = `Authentication error`;

}

res.status(status).send(result);

}).catch(err => {

status = 500;

result.status = status;

result.error = err;

res.status(status).send(result);

});

} else {

status = 404;

result.status = status;

result.error = err;

res.status(status).send(result);

}

});

} else {

status = 500;

result.status = status;

result.error = err;

res.status(status).send(result);

}

});

}Once we verify that a user is who they say they are, we create a token and pass it to our server response. If something goes wrong, we pass back an error as the response.

Now, we get a token every time we successfully log in a user. Yaaay!

Express middleware

An express middleware function is a function that gets triggered when a route pattern is matched in our request uri. All middleware have access to the request and response objects and can call the next()function to pass execution onto the subsequent middleware function.

Believe it or not, we’ve written out several already. Don’t believe me? I’ll show you.

Bodyparser and morgan are both middleware that act on all our routes.

When we call the app.use function without the specifying the first parameter, we’re esentially doing this:

app.use(bodyParser.json());

// This is equivalent to

app.use('/', bodyParser.json());

if (environment !== 'production') {

app.use(logger('dev'));

// and this

app.use('/', logger('dev'));

}

// Here, we've specified the pattern we'd like to be matched from our request's uri

app.use('/api/v1', (req, res, next) => {

res.send('Hello');

// We call next to hand execution over to the next middleware

next();

});Hold that thought and for now, let’s create a controller function that will get all users from our users collection.

controllers/users.js

getAll: (req, res) => {

mongoose.connect(connUri, { useNewUrlParser: true }, (err) => {

User.find({}, (err, users) => {

if (!err) {

res.send(users);

} else {

console.log('Error', err);

}

});

});

}Add our new controller to our routing function.

routes/users.js

const controller = require('../controllers/users');

module.exports = (router) => {

router.route('/users')

.post(controller.add)

.get(controller.getAll); // This route will be protected shortly

router.route('/login')

.post(controller.login);

};Have you noticed that our controllers are esentially middleware functions passed to our other routing middleware? Above we’ve just added middleware our controller that will handle GET requests made to /users. However, we haven’t protected our route yet.

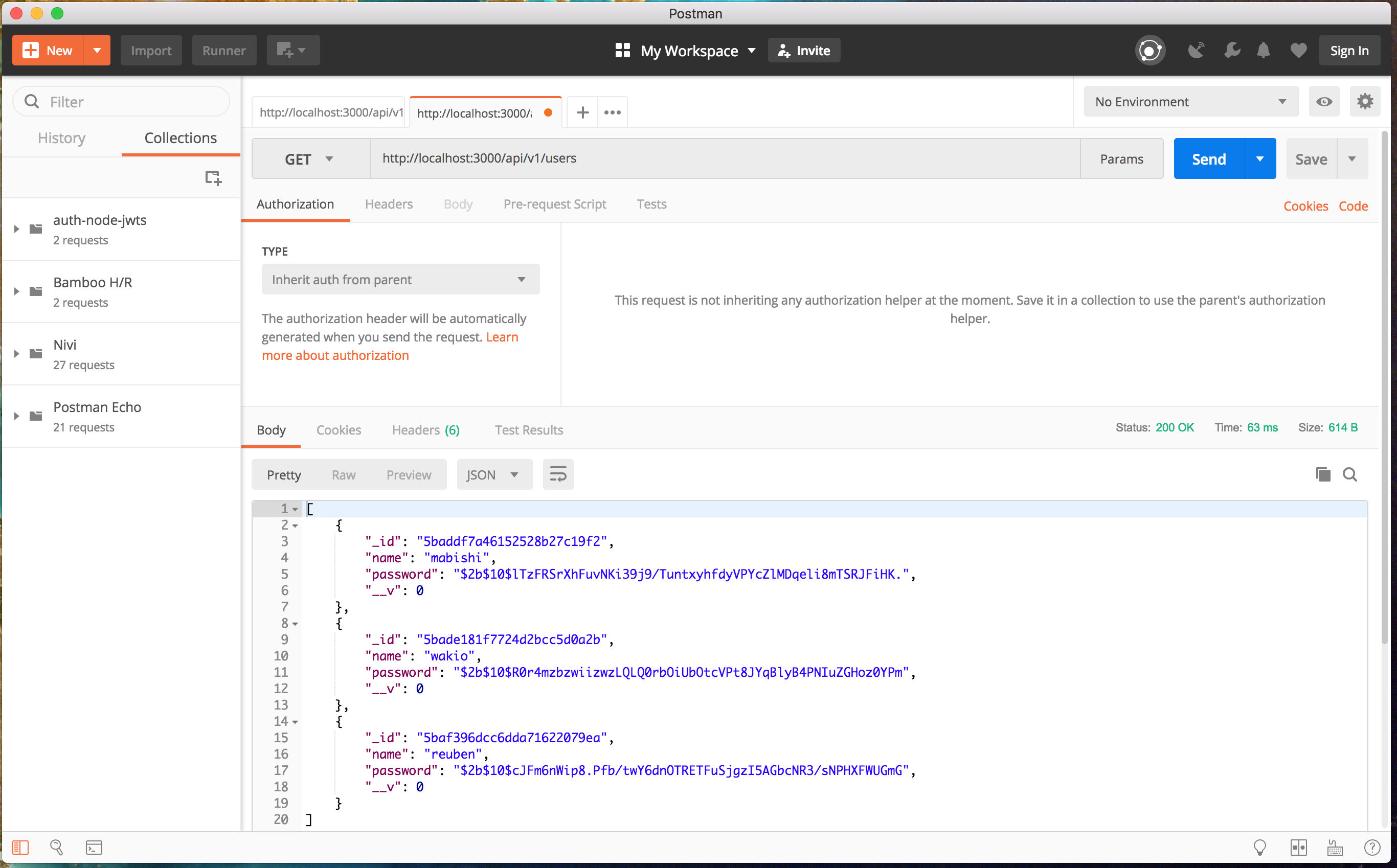

If we make a GET request to /users, here’s what happens.

But we wouldn’t want just any user to access a list of all our users. So, let’s create an admin user then check if they have a token before we allow access to this functionality.

Now, finally, let’s write out middleware to validate that a user has a valid token (issued by us and not expired) before we allow access to certain routes on our application.

utils.js

const jwt = require('jsonwebtoken');

module.exports = {

validateToken: (req, res, next) => {

const authorizationHeaader = req.headers.authorization;

let result;

if (authorizationHeaader) {

const token = req.headers.authorization.split(' ')[1]; // Bearer <token>

const options = {

expiresIn: '2d',

issuer: 'https://scotch.io'

};

try {

// verify makes sure that the token hasn't expired and has been issued by us

result = jwt.verify(token, process.env.JWT_SECRET, options);

// Let's pass back the decoded token to the request object

req.decoded = result;

// We call next to pass execution to the subsequent middleware

next();

} catch (err) {

// Throw an error just in case anything goes wrong with verification

throw new Error(err);

}

} else {

result = {

error: `Authentication error. Token required.`,

status: 401

};

res.status(401).send(result);

}

}

};Let’s add our function to our router so that it’s called before our getAll controller. If validateToken throws an error, controller.getAll won’t be called. Also, if it sends a response with an error, since we haven’t called next in our else block, getAll won’t be called either.

routes/users.js

const controller = require('../controllers/users');

const validateToken = require('../utils').validateToken;

module.exports = (router) => {

router.route('/users')

.post(controller.add)

.get(validateToken, controller.getAll); // This route is now protected

router.route('/login')

.post(controller.login);

};If we leave it as is, all users with a token will be able to access a list of our users but, we only want admins to do this. Let’s make a few final tweaks to our controller to achieve this.

controllers/users.js

getAll: (req, res) => {

mongoose.connect(connUri, { useNewUrlParser: true }, (err) => {

let result = {};

let status = 200;

if (!err) {

const payload = req.decoded;

// TODO: Log the payload here to verify that it's the same payload

// we used when we created the token

// console.log('PAYLOAD', payload);

if (payload && payload.user === 'admin') {

User.find({}, (err, users) => {

if (!err) {

result.status = status;

result.error = err;

result.result = users;

} else {

status = 500;

result.status = status;

result.error = err;

}

res.status(status).send(result);

});

} else {

status = 401;

result.status = status;

result.error = `Authentication error`;

res.status(status).send(result);

}

} else {

status = 500;

result.status = status;

result.error = err;

res.status(status).send(result);

}

});

}As you can see below, if we don’t pass a token in our authorization headers, we’re refused access.

Here’s what happens when we pass an invalid token.

There it is, our middlware is working as intended. Congratulations!

When we pass the token we got from logging in as our admin, we’re allowed to retrieve our users list.

Conclusion

We’ve covered a lot in this article. As a recap, we’ve learned:

- What express middleware is and its basics.

- How to create and use routes and controllers that work as express middleware.

- How to create and verify user tokens.

- How to protect certain routes in our application with our token middleware.

Feedback

I hope this was helpful. As always, please drop me a line in the comments below if you want to chat, ask me a question or give me some feedback.

Source: Scotch.io