Managing state is not a new thing in software, but it’s still relatively new for building software in JavaScript. Traditionally, we’d keep state within the DOM itself or even assign it to a global object in the window. Now though, we’re spoiled with choices for libraries and frameworks to help us with this. Libraries like Redux, MobX and Vuex make managing cross-component state almost trivial. This is great for an application’s resilience and it works really well with a state-first, reactive framework such as React or Vue.

How do these libraries work though? What would it take to write one ourselves? Turns out, it’s pretty straightforward and there’s an opportunity to learn some really common patterns and also learn about some useful modern APIs that are available to us.

Before we get started, it’s recommended that you have an intermediary knowledge of JavaScript. You should know about data types and ideally, you should have a grasp of some more modern ES6+ JavaScript features. If not, we’ve got your back. It’s also worth noting that I’m not saying that you should replace Redux or MobX with this. We’re working on a little project to skill-up together and, hey, it could definitely power a small application if you were keeping an eye on the size of your JavaScript payload.

Getting started

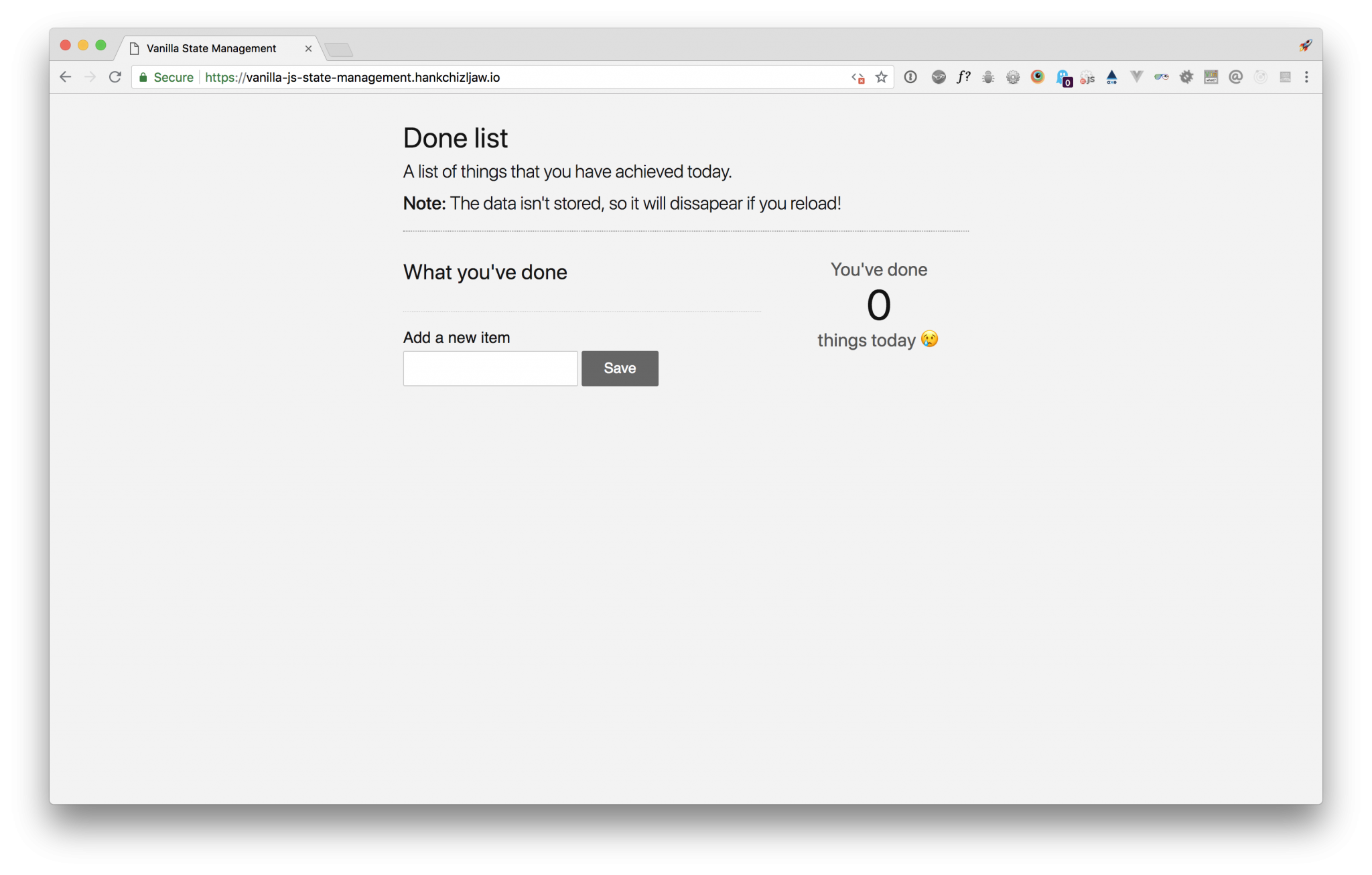

Before we dive into code, take a look at what we’re building. It’s a “done list” that adds up the things you’ve achieved today. It’ll update various elements of the UI like magic — all with no framework dependencies. That’s not the real magic though. Behind the scenes, we’ve got a little state system that’s sitting, waiting for instructions and maintaining a single source of truth in a predictable fashion.

Pretty cool, right? Let’s do some admin first. I’ve put together a bit of a boilerplate so we can keep this tutorial snappy. The first thing you need to do is either clone it from GitHub, or download a ZIP archive and expand it.

Now that you’ve got that going, you’re going to need to run it in a local web server. I like to use a package called http-server for these sort of things, but you can use whatever you want. When you’ve got it running locally, you should see something that looks like this:

Setting up our structure

Open the root folder in your favorite text editor. This time, for me, the root folder is:

~/Documents/Projects/vanilla-js-state-management-boilerplate/You should see a structure that looks a bit like this:

/src

├── .eslintrc

├── .gitignore

├── LICENSE

└── README.mdPub/Sub

Next, open up the src folder and then open up the js folder that lives in there. Make a new folder called lib. Inside that, make a new file called pubsub.js.

The structure of your js directory should look like this:

/js

├── lib

└── pubsub.jsOpen up pubsub.js because we’re going to make a little Pub/Sub pattern, which is short for “Publish/Subscribe.” We’re creating the functionality that allows other parts of our application to subscribe to named events. Another part of the application can then publish those events, often with some sort of relevant payload.

Pub/Sub is sometimes hard to grasp, so how about an analogy? Imagine you work in a restaurant and your customers have a starter and a main course. If you’ve ever worked in a kitchen, you’ll know that when the server clears the starters, they let the chefs know which table’s starters are cleared. This is a cue to start on the main courses for that table. In a big kitchen, there are a few chefs who will probably be on different dishes. They’re all subscribed to the cue from the server that the customers have finished their starters, so they know to do their function, which is to prepare the main course. So, you’ve got multiple chefs waiting on the same cue (named event) to do different functions (callback) to each other.

Hopefully thinking of it like that helps it make sense. Let’s move on!

The PubSub pattern loops through all of the subscriptions and fires their callbacks with that payload. It’s a great way of creating a pretty elegant reactive flow for your app and we can do it with only a few lines of code.

Add the following to pubsub.js:

export default class PubSub {

constructor() {

this.events = {};

}

}What we’ve got there is a fresh new class and we’re setting this.events as a blank object by default. The this.events object will hold our named events.

After the constructor’s closing bracket, add the following:

subscribe(event, callback) {

let self = this;

if(!self.events.hasOwnProperty(event)) {

self.events[event] = [];

}

return self.events[event].push(callback);

}This is our subscribe method. You pass a string event, which is the event’s unique name and a callback function. If there’s not already a matching event in our events collection, we create it with a blank array so we don’t have to type check it later. Then, we push the callback into that collection. If it already existed, this is all the method would do. We return the length of the events collection, because it might be handy for someone to know how many events exist.

Now that we’ve got our subscribe method, guess what comes next? You know it: the publish method. Add the following after your subscribe method:

publish(event, data = {}) {

let self = this;

if(!self.events.hasOwnProperty(event)) {

return [];

}

return self.events[event].map(callback => callback(data));

}This method first checks to see if the passed event exists in our collection. If not, we return an empty array. No dramas. If there is an event, we loop through each stored callback and pass the data into it. If there are no callbacks (which shouldn’t ever be the case), it’s all good, because we created that event with an empty array in the subscribe method.

That’s it for PubSub. Let’s move on to the next part!

The core Store object

Now that we’ve got our Pub/Sub module, we’ve got our only dependency for the meat‘n’taters of this little application: the Store. We’ll go ahead and start fleshing that out now.

Let’s first outline what this does.

The Store is our central object. Each time you see @import store from '../lib/store.js, you’ll be pulling in the object that we’re going to write. It’ll contain a state object that, in turn, contains our application state, a commit method that will call our >mutations, and lastly, a dispatch function that will call our actions. Amongst this and core to the Store object, there will be a Proxy-based system that will monitor and broadcast state changes with our PubSub module.

Start off by creating a new directory in your js directory called store. In there, create a new file called store.js. Your js directory should now look like this:

/js

└── lib

└── pubsub.js

└──store

└── store.jsOpen up store.js and import our Pub/Sub module. To do that, add the following right at the top of the file:

import PubSub from '../lib/pubsub.js';For those who work with ES6 regularly, this will be very recognizable. Running this sort of code without a bundler will probably be less recognizable though. There’s a heck of a lot of support already for this approach, too!

Next, let’s start building out our object. Straight after the import, add the following to store.js:

export default class Store {

constructor(params) {

let self = this;

}

}This is all pretty self-explanatory, so let’s add the next bit. We’re going to add default objects for state, actions, and mutations. We’re also adding a status element that we’ll use to determine what the object is doing at any given time. This goes right after let self = this;:

self.actions = {};

self.mutations = {};

self.state = {};

self.status = 'resting';Straight after that, we’ll create a new PubSub instance that will be attached the Store as an events element:

self.events = new PubSub();Next, we’re going to search the passed params object to see if any actions or mutations were passed in. When the Store object is instantiated, we can pass in an object of data. Included in that can be a collection of actions and mutations that control the flow of data in our store. The following code comes next right after the last line that you added:

if(params.hasOwnProperty('actions')) {

self.actions = params.actions;

}

if(params.hasOwnProperty('mutations')) {

self.mutations = params.mutations;

}That’s all of our defaults set and nearly all of our potential params set. Let’s take a look at how our Store object keeps track of all of the changes. We’re going to use a Proxy to do this. What the Proxy does is essentially work on behalf of our state object. If we add a get trap, we can monitor every time that the object is asked for data. Similarly with a set trap, we can keep an eye on changes that are made to the object. This is the main part we’re interested in today. Add the following straight after the last lines that you added and we’ll discuss what it’s doing:

self.state = new Proxy((params.state || {}), {

set: function(state, key, value) {

state[key] = value;

console.log(`stateChange: ${key}: ${value}`);

self.events.publish('stateChange', self.state);

if(self.status !== 'mutation') {

console.warn(`You should use a mutation to set ${key}`);

}

self.status = 'resting';

return true;

}

});What’s happening here is we’re trapping the state object set operations. That means that when a mutation runs something like state.name = 'Foo' , this trap catches it before it can be set and provides us an opportunity to work with the change or even reject it completely. In our context though, we’re setting the change and then logging it to the console. We’re then publishing a stateChange event with our PubSub module. Anything subscribed to that event’s callback will be called. Lastly, we’re checking the status of Store. If it’s not currently running a mutation, it probably means that the state was updated manually. We add a little warning in the console for that to give the developer a little telling off.

There’s a lot going on there, but I hope you’re starting to see how this is all coming together and importantly, how we’re able to maintain state centrally, thanks to Proxy and Pub/Sub.

Dispatch and commit

Now that we’ve added our core elements of the Store, let’s add two methods. One that will call our actions named dispatch and another that will call our mutations called commit. Let’s start with dispatch by adding this method after your constructor in store.js:

dispatch(actionKey, payload) {

let self = this;

if(typeof self.actions[actionKey] !== 'function') {

console.error(`Action "${actionKey} doesn't exist.`);

return false;

}

console.groupCollapsed(`ACTION: ${actionKey}`);

self.status = 'action';

self.actions[actionKey](self, payload);

console.groupEnd();

return true;

}The process here is: look for an action and, if it exists, set a status and call the action while creating a logging group that keeps all of our logs nice and neat. Anything that is logged (like a mutation or Proxy log) will be kept in the group that we define. If no action is set, it’ll log an error and bail. That was pretty straightforward, and the commit method is even more straightforward.

Add this after your dispatch method:

commit(mutationKey, payload) {

let self = this;

if(typeof self.mutations[mutationKey] !== 'function') {

console.log(`Mutation "${mutationKey}" doesn't exist`);

return false;

}

self.status = 'mutation';

let newState = self.mutations[mutationKey](self.state, payload);

self.state = Object.assign(self.state, newState);

return true;

}This method is pretty similar, but let’s run through the process anyway. If the mutation can be found, we run it and get our new state from its return value. We then take that new state and merge it with our existing state to create an up-to-date version of our state.

With those methods added, our Store object is pretty much complete. You could actually modular-ize this application now if you wanted because we’ve added most of the bits that we need. You could also add some tests to check that everything run as expected. But I’m not going to leave you hanging like that. Let’s make it all actually do what we set out to do and continue with our little app!

Creating a base component

To communicate with our store, we’ve got three main areas that update independently based on what’s stored in it. We’re going to make a list of submitted items, a visual count of those items, and another one that’s visually hidden with more accurate information for screen readers. These all do different things, but they would all benefit from something shared to control their local state. We’re going to make a base component class!

First up, let’s create a file. In the lib directory, go ahead and create a file called component.js. The path for me is:

~/Documents/Projects/vanilla-js-state-management-boilerplate/src/js/lib/component.jsOnce that file is created, open it and add the following:

import Store from '../store/store.js';

export default class Component {

constructor(props = {}) {

let self = this;

this.render = this.render || function() {};

if(props.store instanceof Store) {

props.store.events.subscribe('stateChange', () => self.render());

}

if(props.hasOwnProperty('element')) {

this.element = props.element;

}

}

}Let’s talk through this chunk of code. First up, we’re importing the Store class. This isn’t because we want an instance of it, but more for checking one of our properties in the constructor. Speaking of which, in the constructor we’re looking to see if we’ve got a render method. If this Component class is the parent of another class, then that will have likely set its own method for render. If there is no method set, we create an empty method that will prevent things from breaking.

After this, we do the check against the Store class like I mentioned above. We do this to make sure that the store prop is a Store class instance so we can confidently use its methods and properties. Speaking of which, we’re subscribing to the global stateChange event so our object can react. This is calling the render function each time the state changes.

That’s all we need to write for that class. It’ll be used as a parent class that other components classes will extend. Let’s crack on with those!

Creating our components

Like I said earlier, we’ve got three components to make and their all going to extend the base Component class. Let’s start off with the biggest one: the list of items!

In your js directory, create a new folder called components and in there create a new file called list.js. For me the path is:

~/Documents/Projects/vanilla-js-state-management-boilerplate/src/js/component/list.jsOpen up that file and paste this whole chunk of code in there:

import Component from '../lib/component.js';

import store from '../store/index.js';

export default class List extends Component {

constructor() {

super({

store,

element: document.querySelector('.js-items')

});

}

render() {

let self = this;

if(store.state.items.length === 0) {

self.element.innerHTML = `<p class="no-items">You've done nothing yet ?</p>`;

return;

}

self.element.innerHTML = `

<ul class="app__items">

${store.state.items.map(item => {

return `

<li>${item}<button aria-label="Delete this item">×</button></li>

`

}).join('')}

</ul>

`;

self.element.querySelectorAll('button').forEach((button, index) => {

button.addEventListener('click', () => {

store.dispatch('clearItem', { index });

});

});

}

};I hope that code is pretty self-explanatory after what we’ve learned earlier in this tutorial, but let’s skim through it anyway. We start off by passing our Store instance up to the Component parent class that we are extending. This is the Component class that we’ve just written.

After that, we declare our render method that gets called each time the stateChange Pub/Sub event happens. In this render method we put out either a list of items, or a little notice if there are no items. You’ll also notice that each button has an event attached to it and they dispatch and action within our store. This action doesn’t exist yet, but we’ll get to it soon.

Next up, create two more files. These are two new components, but they’re tiny — so we’re just going to paste some code in them and move on.

First, create count.js in your component directory and paste the following in it:

import Component from '../lib/component.js';

import store from '../store/index.js';

export default class Count extends Component {

constructor() {

super({

store,

element: document.querySelector('.js-count')

});

}

render() {

let suffix = store.state.items.length !== 1 ? 's' : '';

let emoji = store.state.items.length > 0 ? '?' : '?';

this.element.innerHTML = `

<small>You've done</small>

${store.state.items.length}

<small>thing${suffix} today ${emoji}</small>

`;

}

}Looks pretty similar to list, huh? There’s nothing in here that we haven’t already covered, so let’s add another file. In the same components directory add a status.js file and paste the following in it:

import Component from '../lib/component.js';

import store from '../store/index.js';

export default class Status extends Component {

constructor() {

super({

store,

element: document.querySelector('.js-status')

});

}

render() {

let self = this;

let suffix = store.state.items.length !== 1 ? 's' : '';

self.element.innerHTML = `${store.state.items.length} item${suffix}`;

}

}Again, we’ve covered everything in there, but you can see how handy it is having a base Component to work with, right? That’s one of the many benefits of Object-orientated Programming, which is what most of this tutorial is based on.

Finally, let’s check that your js directory is looking right. This is the structure of where we’re currently at:

/src

├── js

│ ├── components

│ │ ├── count.js

│ │ ├── list.js

│ │ └── status.js

│ ├──lib

│ │ ├──component.js

│ │ └──pubsub.js

└───── store

└──store.js

└──main.jsLet’s wire it up

Now that we’ve got our front-end components and our main Store, all we’ve got to do is wire it all up.

We’ve got our store system and the components to render and interact with its data. Let’s now wrap up by hooking up the two separate ends of the app and make the whole thing work together. We’ll need to add an initial state, some actions and some mutations. In your store directory, add a new file called state.js. For me it’s like this:

~/Documents/Projects/vanilla-js-state-management-boilerplate/src/js/store/state.jsOpen up that file and add the following:

export default {

items: [

'I made this',

'Another thing'

]

};This is pretty self-explanatory. We’re adding a default set of items so that on first-load, our little app will be fully interactive. Let’s move on to some actions. In your store directory, create a new file called actions.js and add the following to it:

export default {

addItem(context, payload) {

context.commit('addItem', payload);

},

clearItem(context, payload) {

context.commit('clearItem', payload);

}

};The actions in this app are pretty minimal. Essentially, each action is passing a payload to a mutation, which in turn, commits the data to store. The context, as we learned earlier, is the instance of the Store class and the payload is passed in by whatever dispatches the action. Speaking of mutations, let’s add some. In this same directory add a new file called mutations.js. Open it up and add the following:

export default {

addItem(state, payload) {

state.items.push(payload);

return state;

},

clearItem(state, payload) {

state.items.splice(payload.index, 1);

return state;

}

};Like the actions, these mutations are minimal. In my opinion, your mutations should always be simple because they have one job: mutate the store’s state. As a result, these examples are as complex as they should ever be. Any proper logic should happen in your actions. As you can see for this system, we return the new version of the state so that the Store`'s <code>commit method can do its magic and update everything. With that, the main elements of the store system are in place. Let’s glue them together with an index file.

In the same directory, create a new file called index.js. Open it up and add the following:

import actions from './actions.js';

import mutations from './mutations.js';

import state from './state.js';

import Store from './store.js';

export default new Store({

actions,

mutations,

state

});All this file is doing is importing all of our store pieces and glueing them all together as one succinct Store instance. Job done!

The final piece of the puzzle

The last thing we need to put together is the main.js file that we included in our index.html page waaaay up at the start of this tutorial. Once we get this sorted, we’ll be able to fire up our browsers and enjoy our hard work! Create a new file called main.js at the root of your js directory. This is how it looks for me:

~/Documents/Projects/vanilla-js-state-management-boilerplate/src/js/main.jsOpen it up and add the following:

import store from './store/index.js';

import Count from './components/count.js';

import List from './components/list.js';

import Status from './components/status.js';

const formElement = document.querySelector('.js-form');

const inputElement = document.querySelector('#new-item-field');So far, all we’re doing is pulling in dependencies that we need. We’ve got our Store, our front-end components and a couple of DOM elements to work with. Let’s add this next bit to make the form interactive, straight under that code:

formElement.addEventListener('submit', evt => {

evt.preventDefault();

let value = inputElement.value.trim();

if(value.length) {

store.dispatch('addItem', value);

inputElement.value = '';

inputElement.focus();

}

});What we’re doing here is adding an event listener to the form and preventing it from submitting. We then grab the value of the textbox and trim any whitespace off it. We do this because we want to check if there’s actually any content to pass to the store next. Finally, if there’s content, we dispatch our addItem action with that content and let our shiny new store deal with it for us.

Let’s add some more code to main.js. Under the event listener, add the following:

const countInstance = new Count();

const listInstance = new List();

const statusInstance = new Status();

countInstance.render();

listInstance.render();

statusInstance.render();All we’re doing here is creating new instances of our components and calling each of their render methods so that we get our initial state on the page.

With that final addition, we are done!

Open up your browser, refresh and bask in the glory of your new state managed app. Go ahead and add something like “Finished this awesome tutorial” in there. Pretty neat, huh?

Next steps

There’s a lot of stuff you could do with this little system that we’ve put together. Here are some ideas for taking it further on your own:

- You could implement some local storage to maintain state, even when you reload

- You could pull out the front-end of this and have a little state system for your projects

- You could continue to develop the front-end of this app and make it look awesome. (I’d be really interested to see your work, so please share!)

- You could work with some remote data and maybe even an API

- You could take what you’ve learned about

Proxyand the Pub/Sub pattern and develop those transferable skills further

Wrapping up

Thanks for learning about how these state systems work with me. The big, popular ones are much more complex and smarter that what we’ve done — but it’s still useful to get an idea of how these systems work and unravel the mystery behind them. It’s also useful to learn how powerful JavaScript can be with no frameworks whatsoever.

If you want a finished version of this little system, check out this GitHub repository. You can also see a demo here.

If you develop on this further, I’d love to see it, so hit me up on Twitter or post in the comments below if you do!

Source: CSS-tricks.com