You know how some sites and web apps have that neat native feel when transitioning between two pages or views? Sarah Drasner has shown some good examples and even a Vue library to boot.

These animations are the type of features that can turn a good user experience into a great one. But to achieve this in a React stack, it is necessary to couple crucial parts in your application: the routing logic and the animation tooling.

Let’s start with animations. We’ll be building with React, and there are great options out there for us to leverage. Notably, the react-transition-group is the official package that handles elements entering and leaving the DOM. Let’s explore some relatively straightforward patterns we can apply, even to existing components.

Transitions using react-transition-group

First, let’s get familiar with the react-transition-group library to examine how we can use it for elements entering and leaving the DOM.

Single components transitions

As a simple example of a use case, we can try to animate a modal or dialog — you know, the type of element that benefits from animations that allow it enter and leave smoothly.

A dialog component might look something like this:

import React from "react";

class Dialog extends React.Component {

render() {

const { isOpen, onClose, message } = this.props;

return (

isOpen && (

<div className="dialog--overlay" onClick={onClose}>

<div className="dialog">{message}</div>

</div>

)

);

}

}Notice we are using the isOpen prop to determine whether the component is rendered or not. Thanks to the simplicity of the recently modified API provided by react-transition-group module, we can add a CSS-based transition to this component without much overhead.

First thing we need is to wrap the entire component in another TransitionGroup component. Inside, we keep the prop to mount or unmount the dialog, which we are wrapping in a CSSTransition.

import React from "react";

import { TransitionGroup, CSSTransition } from "react-transition-group";

class Dialog extends React.Component {

render() {

const { isOpen, onClose, message } = this.props;

return (

<TransitionGroup component={null}>

{isOpen && (

<CSSTransition classNames="dialog" timeout={300}>

<div className="dialog--overlay" onClick={onClose}>

<div className="dialog">{message}</div>

</div>

</CSSTransition>

)}

</TransitionGroup>

);

}

}Every time isOpen is modified, a sequence of class names changes will happen in the dialog’s root element.

If we set the classNames prop to "fade", then fade-enter will be added immediately before the element mounts and then fade-enter-active when the transition kicks off. We should see fade-enter-done when the transition finishes, based on the timeout that was set. Exactly the same will happen with the exit class name group at the time the element is about to unmount.

This way, we can simply define a set of CSS rules to declare our transitions.

.dialog-enter {

opacity: 0.01;

transform: scale(1.1);

}

.dialog-enter-active {

opacity: 1;

transform: scale(1);

transition: all 300ms;

}

.dialog-exit {

opacity: 1;

transform: scale(1);

}

.dialog-exit-active {

opacity: 0.01;

transform: scale(1.1);

transition: all 300ms;

}JavaScript Transitions

If we want to orchestrate more complex animations using a JavaScript library, then we can use the Transition component instead.

This component doesn’t do anything for us like the CSSTransition did, but it does expose hooks on each transition cycle. We can pass methods to each hook to run calculations and animations.

<TransitionGroup component={null}>

{isOpen && (

<Transition

onEnter={node => animateOnEnter(node)}

onExit={node => animateOnExit(node)}

timeout={300}

>

<div className="dialog--overlay" onClick={onClose}>

<div className="dialog">{message}</div>

</div>

</Transition>

)}

</TransitionGroup>Each hook passes the node to the callback as a first argument — this gives control for any mutation we want when the element mounts or unmounts.

Routing

The React ecosystem offers plenty of router options. I’m gonna use react-router-dom since it’s the most popular choice and because most React developers are familiar with the syntax.

Let’s start with a basic route definition:

import React, { Component } from 'react'

import { BrowserRouter, Switch, Route } from 'react-router-dom'

import Home from '../views/Home'

import Author from '../views/Author'

import About from '../views/About'

import Nav from '../components/Nav'

class App extends Component {

render() {

return (

<BrowserRouter>

<div className="app">

<Switch>

<Route exact path="/" component={Home}/>

<Route path="/author" component={Author} />

<Route path="/about" component={About} />

</Switch>

</div>

</BrowserRouter>

)

}

}We want three routes in this application: home, author and about.

The BrowserRouter component handles the browser’s history updates, while Switch decides which Route element to render depending on the path prop.

Oil and water

While both react-transition-group and react-router-dom are great and handy packages for their intended uses, mixing them together can break their functionality.

For example, the Switch component in react-router-dom expects direct Route children and the TransitionGroup components in react-transition-group expect CSSTransition or Transition components to be direct children of it too. So, we’re unable to wrap them the way we did earlier.

We also cannot toggle views with the same boolean approach as before since it’s handled internally by the react-router-dom logic.

React keys to the rescue

Although the solution might not be as clean as our previous examples, it is possible to use the libraries together. The first thing we need to do is to move our routes declaration to a render prop.

<BrowserRouter>

<div className="app">

<Route render={(location) => {

return (

<Switch location={location}>

<Route exact path="/" component={Home}/>

<Route path="/author" component={Author} />

<Route path="/about" component={About} />

</Switch>

)}

/>

</BrowserRouter>Nothing has changed as far as functionality. The difference is that we are now in control of what gets rendered every time the location in the browser changes.

Also, react-router-dom provides a unique key in the location object every time this happens.

In case you are not familiar with them, React keys identify elements in the virtual DOM tree. Most times, we don’t need to indicate them since React will detect which part of the DOM should change and then patch it.

<Route render={({ location }) => {

const { pathname, key } = location

return (

<TransitionGroup component={null}>

<Transition

key={key}

appear={true}

onEnter={(node, appears) => play(pathname, node, appears)}

timeout={{enter: 750, exit: 0}}

>

<Switch location={location}>

<Route exact path="/" component={Home}/>

<Route path="/author" component={Author} />

<Route path="/about" component={About} />

</Switch>

</Transition>

</TransitionGroup>

)

}}/>Constantly changing the key of an element — even when its children or props haven’t been modified — will force React to remove it from the DOM and remount it. This helps us emulate the boolean toggle approach we had before and it’s important for us here because we can place a single Transition element and reuse it for all of our view transitions, allowing us to mix routing and transition components.

Inside the animation function

Once the transition hooks are called on each location change, we can run a method and use any animation library to build more complex scenes for our transitions.

export const play = (pathname, node, appears) => {

const delay = appears ? 0 : 0.5

let timeline

if (pathname === '/')

timeline = getHomeTimeline(node, delay)

else

timeline = getDefaultTimeline(node, delay)

timeline.play()

}Our play function will build a GreenSock timeline here depending on the pathname, and we can set as many transitions as we want for each different routes.

Once the timeline is built for the current pathname, we play it.

const getHomeTimeline = (node, delay) => {

const timeline = new Timeline({ paused: true });

const texts = node.querySelectorAll('h1 > div');

timeline

.from(node, 0, { display: 'none', autoAlpha: 0, delay })

.staggerFrom(texts, 0.375, { autoAlpha: 0, x: -25, ease: Power1.easeOut }, 0.125);

return timeline

}Each timeline method digs into the DOM nodes of the view and animates them. You can use other animation libraries instead of GreenSock, but the important detail is that we build the timeline beforehand so that our main play method can decide which one should run for each route.

I’ve used this approach on lots of projects, and though it doesn’t present obvious performance issues for inner navigations, I did notice a concurrency issue between the browser’s initial DOM tree build and the first route animation. This caused a visual lag on the animation for the first load of the application.

To make sure animations are smooth in each stage of the application, there’s one last thing we can do.

Profiling the initial load

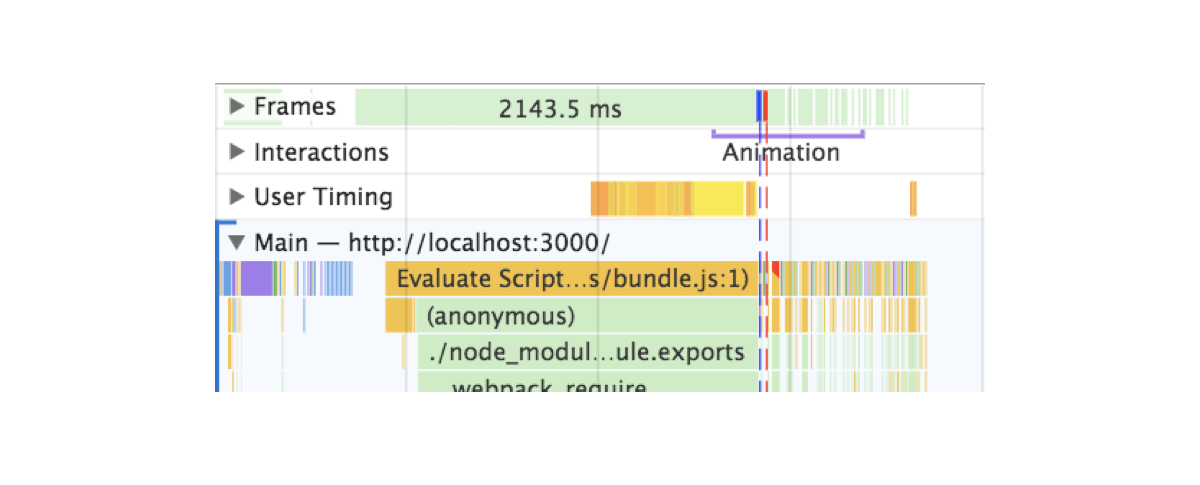

Here’s what I found when auditing the application in Chrome DevTools after a hard refresh:

You can see two lines: one blue and one red. Blue represents the load event and red the DOMContentLoaded. Both intersect the execution of the initial animations.

These lines are indicating that elements are animating while the browser hasn’t yet finished building the entire DOM tree or it’s parsing resources. Animations account for big performance hits. If we want anything else to happen, we’d have to wait for the browser to be ready with these heavy and important tasks before running our transitions.

After trying a lot of different approaches, the solution that actually worked was to move the animation after these events — simple as that. The issue is that we can’t rely on event listeners.

window.addEventListener(‘DOMContentLoaded’, () => {

timeline.play()

})If for some reason, the event occurs before we declare the listener, the callback we pass will never run and this could lead to our animations never happening and an empty view.

Since this is a concurrency and asynchronous issue, I decided to rely on promises, but then the question became: how can promises and event listeners be used together?

By creating a promise that gets resolved when the event takes place. That’s how.

window.loadPromise = new Promise(resolve => {

window.addEventListener(‘DOMContentLoaded’, resolve)

})We can put this in the document head or just before the script tag that loads the application bundle. This will make sure the event never happens before the Promise is created.

Plus, doing this allows us to use the globally exposed loadPromise to any animation in our application. Let’s say that we don’t only want to animate the entry view but a cookie banner or the header of the application. We can simply call each of these animations after the promise has resolved using then along with our transitions.

window.loadPromise.then(() => timeline.play())This approach is reusable across the entire codebase, eliminating the issue that would result when an event gets resolved before the animations run. It will defer them until the browser DOMContentLoaded event has passed.

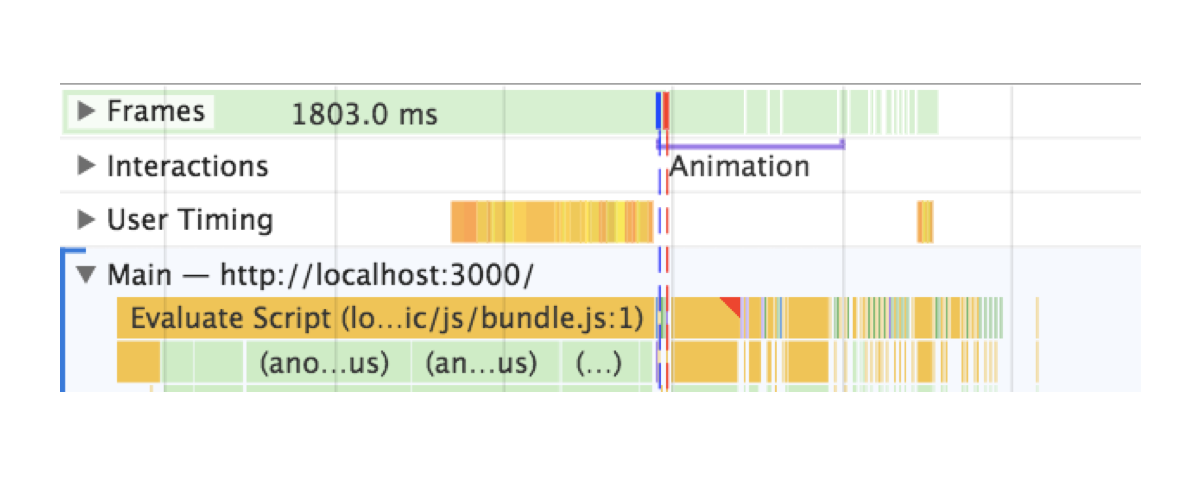

See now that the animation is not kicking off until the red line appears.

The difference is not only on the profiling report — it actually solves an issue we had in a real project.

Wrapping up

In order to act as reminders, I created a list of tips for me that you might find useful as you dig into view transitions in a project:

- When an animation is happening nothing else should be happening. Run animations after all resources, fetching and business logic have completed.

- No animation is better than crappy animations If you can’t achieve a good animation, then removing it is a fair sacrifice. The content is more important and showing it is the priority until a good animation solution is in place.

- Test on slower and older devices. They will make it easier for you to catch spots with weak performance.

- Profile and base your improvements in metrics. Instead of guessing as you go, like I did, see if you can spot where frames are being dropped or if something looks off and attack that issue first.

That’s it! Best of luck with animating view transitions. Please post a comment if this sparked any questions or if you have used transitions in your app that you’d like to share!

Source: CSS-tricks.com